Clos du Tue-Boeuf, in the relatively unknown Cheverny appellation, will never make the next Instagram-famous unicorn bottle, and their wines will never go for hundreds of dollars on the grey market. But Tue-Boeuf is, in their own quiet way, one of the most important estates in the Loire Valley. . For anyone interested in the Loire Valley, natural wine, or just delicious and soulful wine in general, Clos du Tue-Boeuf is an absolute must-buy.

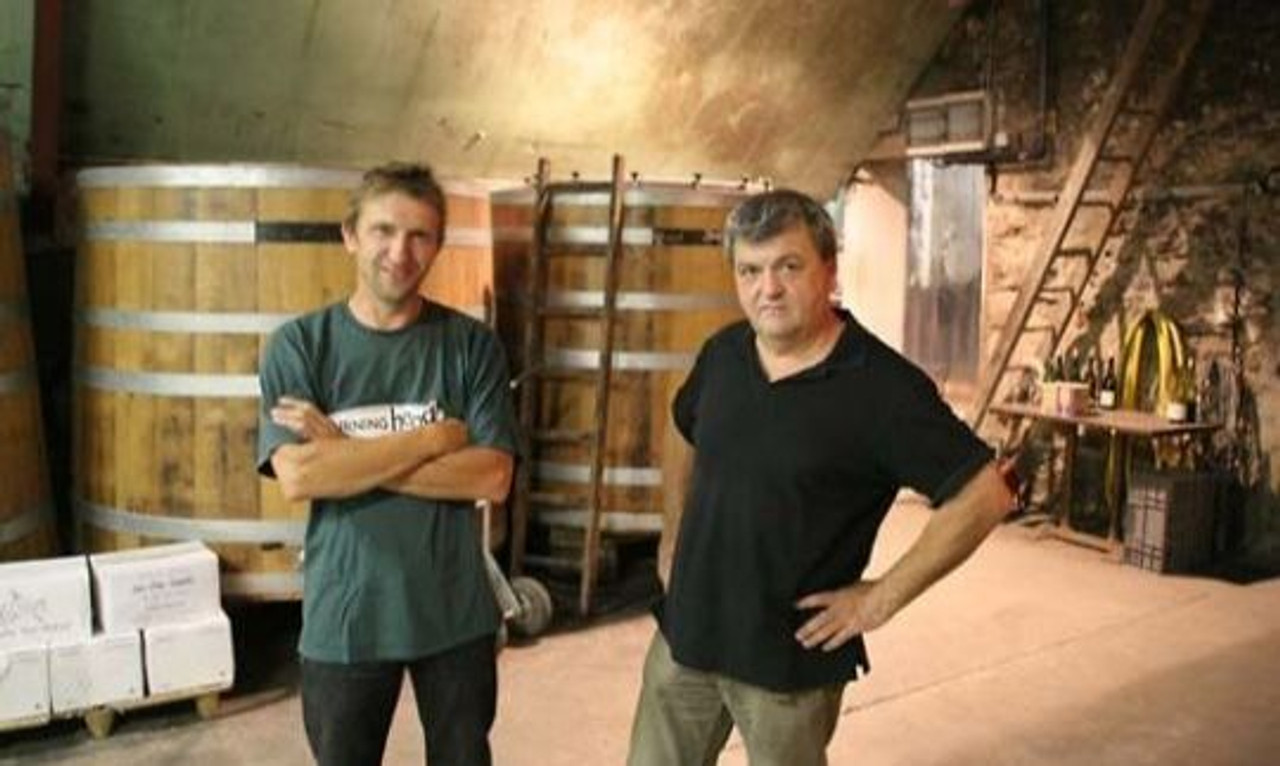

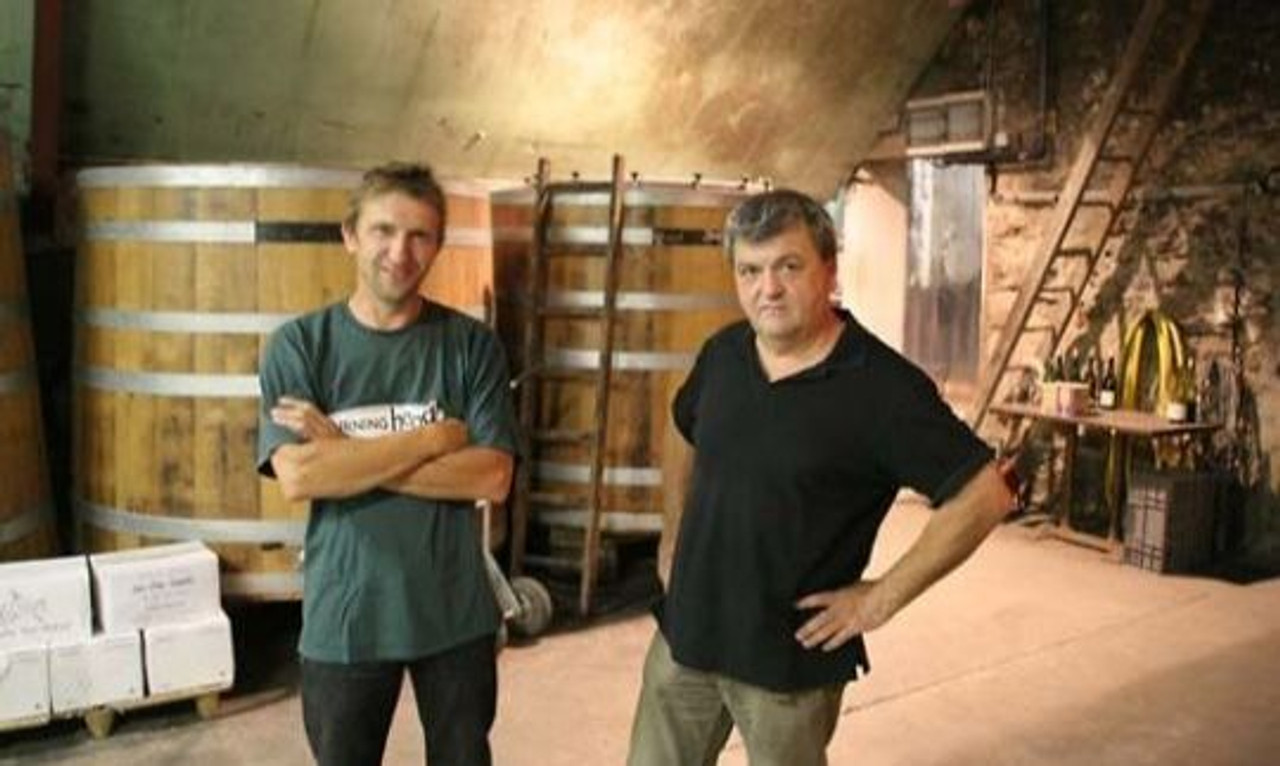

Records mention the Puzelat name and wines being made at the Clos since the 1400s. History says their wines were consumed by the kings of France--but this is no grand estate. It's a tiny family operation, purchased by Jean Puzelat in 1947. Jean's son Jean-Marie took over in 1989 and was joined by his brother Thierry in 1994. It was Thierry who propelled the estate to the forefront of the then-nascent natural wine movement. Thierry had worked for years for the legendary Marcel Lapierre in Beaujolais' Morgon and was inspired to follow the minimal-intervention path laid out by him. Upon arriving at Tue-Boeuf, Thierry converted farming to organics (an easy transition, as his father had never used many chemicals in the first place) and began making wine free of any additions, including sulfur in many cases.

Though the wines fly under the radar of the general public, Tue-Boeuf is one of the underappreciated heroes of the Loire Valley. Their home commune, Cheverny, is a fascinating little region, one with a long history but relatively few quality-minded producers. It's a kind of crossroads, viticulturally speaking, with plantings of the Sauvignon Blanc and Pinot Noir found in Sancerre to the East, and Cabernet Franc and Chenin Blanc found in Vouvray and Chinon to the West. But it also has its own unique varieties, like Pineau d'Aunis, Menu Pineau, Gamay, and Romorantin. The appellation rules have changed frequently over the years and many of these lesser-known varieties have been ripped out, but the Puzelats have protected their plantings of these fantastic grapes, often forgoing appellation labeling to do so. Their work has inspired dozens of growers and winemakers in the Loire to follow in their path.

Thierry Puzelats' history with Marcel Lapierre is apropos. I find the Tue-Boef wines share some kinship with Lapierre's, combining joyful exuberance with terroir-reflective seriousness. Across the board, the wines are delicious and eminently drinkable young, but like Lapierre's wines, will definitely reward a few years in your cellar. As natural wine's popularity has grown exponentially in the years since Tue-Boeuf's arrival, it's helpful to return to (or discover) wines like these to be reminded of why the movement started in the first place: beautiful and unbridled expressions of people, variety, and place.

|

|